Ratanpur in western Nepal’s Tanahun District could be any other village in the country. Here, you neither hear children crackle nor young men sing songs to their beloved, all you hear is the aches and pains of old age. The cuckoo bird is the loudest living soul in the village, but her songs are also drowned when the floodgates of the sky open during the monsoon.

Looking at historic paddy terraces, one can only imagine how lively this place would have been in its heyday. Young men and women would work in the fields and their tunes would reverberate in the surrounding hills. But all that is now a distant dream for Ram Kumari Pandit (60s) and her fellow villagers.

“You don’t find young men here. All of them have left,” says Pandit, “Our sons have migrated abroad to look for jobs. Their wives have left the village in search of a brighter future for their children in cities,” she shares. “They do not see a future for their children in the village and have migrated to cities such as Kathmandu and Pokhara.”

Ram Kumari is one of the thousands of senior citizens who are now in-charge in villages across the country. Just like the young men and women of Ratanpur, more than 1,500 Nepalis, most of them young men, leave the country every day in search of work, and an equal number, if not more, move from the villages to the cities.

The shortage of able-bodied men and women in their prime has had a devastating effect on rural households. The numbers speak for themselves: more than 21 per cent of arable land in the country remained fallow last year, leaving Nepal on rank 81 in the Global Food Security Index.

However, in Ratanpur, the terraces tell a different tale. The village, located around 200 km west of Kathmandu, is where local women have taken up a seemingly impossible mission—to make it profitable for villagers to stay at home rather than go outside seeking for opportunities. Their modus operandi: utilize money from private carbon emitters in Europe to rejuvenate barren land and breath life into the village once again.

It all started in 2015, the year the earthquake caught Nepal unprepared. With rumors of the possibility of an epidemic in Kathmandu, people from outside the Valley returned to their villages to stay there until the situation normalized. This was the time frame that had been closed for ages opened again to let in sunlight and let out the fragrance of freshly-cooked dal bhat (rice and lentils).

“Everyone was in a reflective mood,” remembers Hans-Peter Schmidt, a Swiss scientist who accompanied his friend and forestry scholar Bishnu Hari Pandit to the village in the aftermath of the disaster. The villagers saw what had become of their ancestral land and wanted to do something about it. Many ideas were discussed.

Bishnu Hari explained to the villagers that the barren farms were problematic in many ways. “I told them that when we leave the rice fields fallow, we are not only abandoning our ancestral heritage but also leaving it prone to erosion,” he shares. All this is happening as effects of climate change are already being felt in the hills.

“It was at this moment that the villagers announced they wanted to plant 50,000 trees in the next three years,” says Schmidt, who along with Bishnu Hari was given the responsibility to come-up with a program to turn that dream into a reality. Schmidt and Bishnu Hari, who had been working on implementing ‘biochar’ projects around the country for the past few years, came up with an idea.

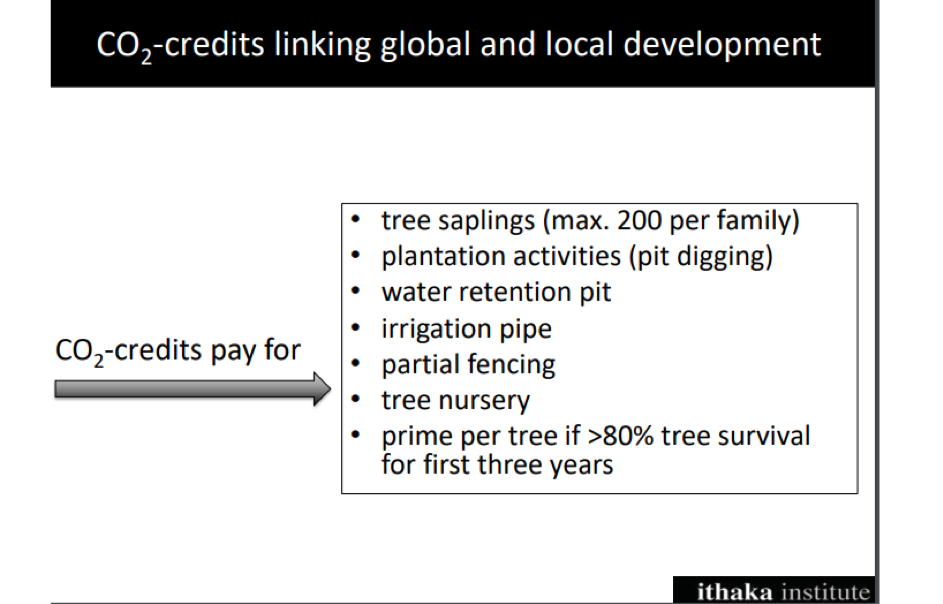

They identified the main challenge. The government did supply a limited number of saplings for free, but their survival rate was pretty low. Local communities wanted to plant trees, but did do not have the money and knowhow to maintain them. The money had to come from somewhere. Schmidt’s idea was to get money from private individuals in Europe who want to offset their daily emissions.

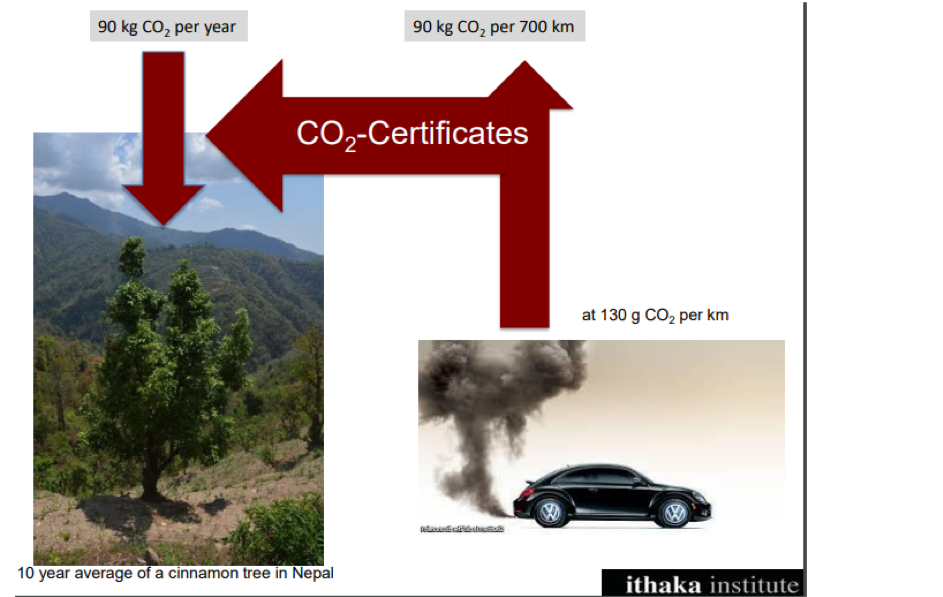

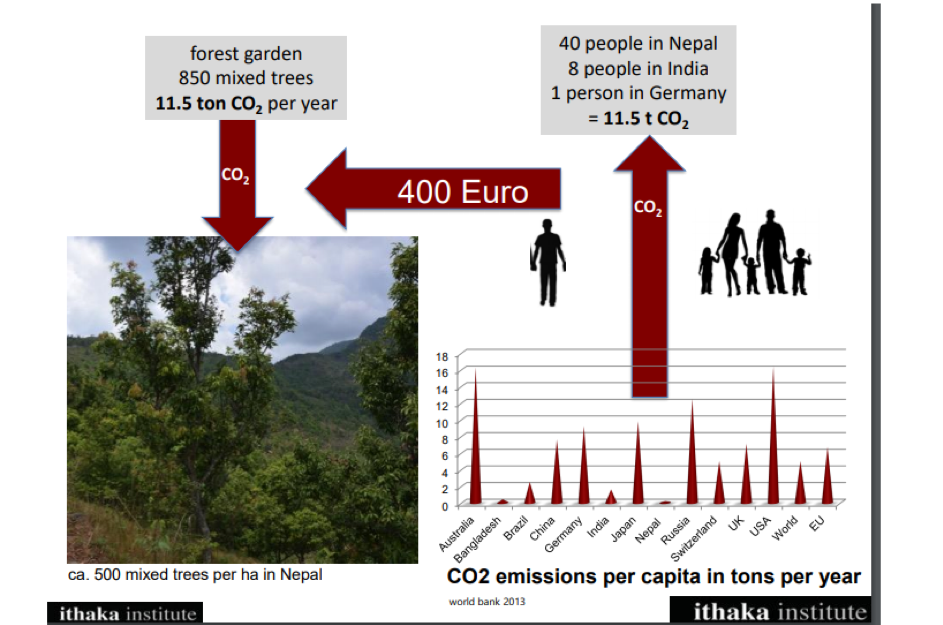

Schmidt and his team members from Ithaka Institute, a scientific organization based in Switzerland and Nepal, decided that under the scheme, private emitters will be charged $35 for every ton of carbon offset by trees in Ratanpur. This would cover all costs to setup the forest gardens and their maintenance for three years. The farmers would receive money for taking care of their trees. Schmidt says that Ithaka calculated the price of carbon by looking at the overall cost of the project and resources needed to sustain it. “The price of carbon is not the same around the world.”

Under the scheme, environment-conscious people like Sibylle Maurer-Wohlatz who lives in Germany pay a certain subscription fee to offset their personal carbon footprint. “I spend as much money as is needed to compensate my personal emissions by letting trees in Nepal grow. Trees are as long as they grow a medium to store carbon. For me, this is a sum of 27 Euro each month,” she tells.

“Because I am still causing CO2 emissions with my way of life, I wanted to compensate in a way that really works. Because the richer countries profit worldwide from the resources of poorer countries, I was very pleased, when Hans Peter Schmidt told me about his project and the intentions to let people compensate their emissions by giving money to plant trees in devastated areas in Nepal and to give small farmers the chance, to stabilize the environment and improve their agricultural conditions.”

According to Ithaka, a total of 25,000 Euro has been spent on the project so far. The 218 farmer families have received 4,800 Euro as carbon money for the 50,000 trees they have planted so far. A total of 21,200 Euro, received as carbon money, was used to procure plants, establish tree nurseries, buy irrigation pipes, water retention pits, and cover plantation and maintenance costs for the project. The plantation activities were also supported by the District Forestry Office, the Hariyo ban program, the Schöck Familienstiftung along with UK Aid.

All planted trees are GIS inventoried—the trees GPS coordinates are recorded and fed into a software–and their yearly biomass carbon uptake is calculated on the base of the average ten-year carbon accumulation.

They planted cinnamon, mulberry, michelia champaca, paulownia, and moringa trees, fruit trees like mango, banana, and citrus as well as a variety of local tree species – all plants that have high commercial or nutrient value. The carbon money was is only intended as a catalyst to establish the forest garden systems. After three years, the income from tree crops (fruits, nuts, medicine, essential oil, silk, perfume, honey, timber, animal fodder) would be by far more than the carbon money.

From the start, the local women took the lead of the initiative. “The local mothers’ group vowed to make the project a success,” remembers Hari Maya Pandit, one of the members. “We realized that keeping the land fallow was a big mistake,” says Ram Kumari Pandit, who is now the chair of the group.

“We started a campaign to plant trees, and we dedicated ourselves to making it a success,” says Ram Kumari Pandit. “In the beginning, people were hesitant to switch from paddy, which they had been growing for centuries, to trees. But soon everyone realized why trees were important,” she shares. Survival rates, which were around 57 per cent in the first year, have gone up to 86 per cent—thanks to the active participation of women, the use of ‘biochar’ and the formation of ‘triade’ groups (see the main article)

Hans Peter Schmidt and Bishnu Hari Pandit had been testing the use of biochar with different crops around Nepal. They had seen that biochar not only helped increase yields, growth and survival rates of trees, but also helped retain carbon (that would otherwise return back to the atmosphere).

As Ratanpur had also been affected by Eupatorium adenophorum the ‘forest killer’ (an invasive shrub), using it to make biochar had dual benefits (i.e. eradicating the invasive plants and sequestering carbon). Similarly, charging the biochar, which would remain in the soil for a long time, with cow urine, boosted the amount of nutrients the young trees receive from the soil.

Although the use of biochar could push the survival rate to 57 per cent, it was the ‘triade’ system that would take it past the 80 per cent mark. Under the triade system, each farmer is made a member of a group of three people who help one another in the farm.

Between 2015 and 2018, a total 218 farmer families in and around Ratanpur planted more than 50,000 trees of multiple species on 50 ha of private land. “We were very excited to prepare biochar, plant the trees and see them grow,” says Surya Kala Gharti. “The whole environment of the village has changed in the last three years,” she adds. “I think these many trees would not have been planted were it not for the mothers’ group,” claims Ram Kumari Pandit. “After the implementation of the project, local water sources, which had dried up, are also coming back to life as the soil retains more moisture.

According to Ithaka, the 50,000 garden trees sequester a minimum of 800 tonnes of carbon per year. It is enough to offset the carbon footprint of 70 Germans or 2,800 Nepalis.

After this year’s rainy season, the series of tree plantations reached its third year and farmers who have received ‘maintenance’ money for their surviving trees will stop doing so from next year on. But are the farmers ready for the switch as Schmidt had imagined in 2015?

The answer seems to be a yes and a no. Ram Kumari Pandit says that a lot of people visit her village these days. “There are times when visitors from different forestry colleges come here to observe what is going on. Some international scholars also come here to spend time,” shares Gharti, who is a member of the local municipal assembly.

The women in the village are thus already earning money from tourisme, even before the products from the forest gardens are sold in the market. There is a steady stream of people who come to visit the village and pay local house owners for bed&breafast. “This was something unexpected for a village like Ratanpur,” says Ram Kumari Pandit. A few months ago, the women’s group received about 2000 Euro for hosting a large group of tourists in their homes.

However, this was not the economic benefit Schmidt had imagined. “We do not know what is to be done with our product. But we are sure that Schmidt and Bishnu Hari Pandit would have thought something about it,” says Gharti.

Schmidt says he wants to create a model in Ratanpur that could be easily replicated in villages in Nepal’s hills. He says that cinnamon oil is in high demand in Europe and he could link up the farmers with interested companies in Europe. But he wants the local products to be consumed locally too which seems to be a big challenge as the women seem to have little idea about processing their raw produce and marketing them outside the village.

The Swiss scientist says Ithaka is working on establishing a distillery to prepare cinnamon oil and it will also help local farmers produce silk, but doing that will also take time. However, large swathes of land in the village is no longer fallow, and that in itself is a big achievement.

“What we want to show is that people in the villages can earn more than people in the cities because production takes place in the villages and cities only consume. This could be the reason, one day, people return to their villages,” he adds. “This is not a development aid project but the creation of a pilot project for climate farming where we try to create and develop an environmental, economic and social model that could be multiplied in many regions of the country and abroad. The main income will be generated through the forest garden products”:

“The carbon payment is only a kind of seed money to allow the implementation of the new agronomic systems.”

The project comes at a time when Nepal is preparing to take advantage of the much-talked-about REDD-Plus arrangement, under which developing countries are to receive money from developed countries for management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks.

“REDD-Plus adopts a similar model to what has been done in Ratanpur,” says Mohan Poudel, a REDD expert. “The other advantage of projects like this is that they reduce the pressure on community forests and encourage private enterprises based on forest products. This is something REDD wants to achieve,” adds Poudel.

“The other positive is that this model has shown that when people have monetary incentive to grow trees on barren land, the survival rates go up. This is something that the government needs to take note as land is being left barren in the hills due to outward migration.”

However, Poudel is a bit skeptical that the model could be replicated at a large scale as there are legal hurdles to doing so. The constitution has placed carbon trading under the ambit of the federal government, and that complicates the matter.

Meanwhile, Ram Kumari Pandit, who still maintains her kitchen garden to get her daily veggies, is happy. She is not waiting for the economic benefits to come to her. “I did not even participate in the campaign for the money. I just wanted our ancestral land to be preserved for posterity and that is what is happening here. If my grandchildren want to return, they will have the option to do that.”

This story was prepared under a grant from Earth Journalism Network.

- Please write us your comment -

×